Phosphorus fertiliser decisions after the drought

Where cash flow is tight, many growers are likely to be looking to reduce costs at sowing time by reducing phosphorus (P) applications on some or all of their paddocks. The hope is that fertiliser phosphorus applied at the start of the 2018 season will still be available to the current crop.

by Jim Laycock, Technical Agronomist, Incitec Pivot Fertilisers

Phosphorus fertiliser investment decisions for 2019 should start with knowing or defining the soil P status from a soil test. If the information is not available, soil test now to find out starting soil P levels.

There are a number of different answers to the ‘how low can I go?’ question and ultimately growers will need to decide for themselves on the right approach for their cropping business. To answer the question, it helps to look at why phosphorus is applied in winter crops in the first place.

- To effectively provide readily available phosphorus to emerging crops

Sowing time is the only opportunity to effectively supply phosphorus to the crop. The most efficient placement of fertiliser phosphorus in broadacre crops is banded with the seed. This enables roots emerging from the seed to contact an area of high phosphorus availability and encourages root proliferation and penetration into the soil below the seed.1

If the crop has enough applied phosphorus at sowing to grow well for the first six weeks, it will have time to access further phosphorus during the season. If the crop is limited by a lack of phosphorus during these early growth stages, this setback will be carried through to maturity and cannot be corrected.

- To maintain and build soil phosphorus fertility to optimum levels

Many soils contain too little phosphorus for healthy cereal crop growth and require regular additions to replace nutrients removed and build soil fertility. When soils are fertilised with phosphorus, the availability of soil P for crop growth is increased. When fertiliser phosphorus is not re-applied regularly, the availability of soil P for crop growth slowly decreases with time, and grain yield responses to applied P inevitably increase.2

- To optimise yields

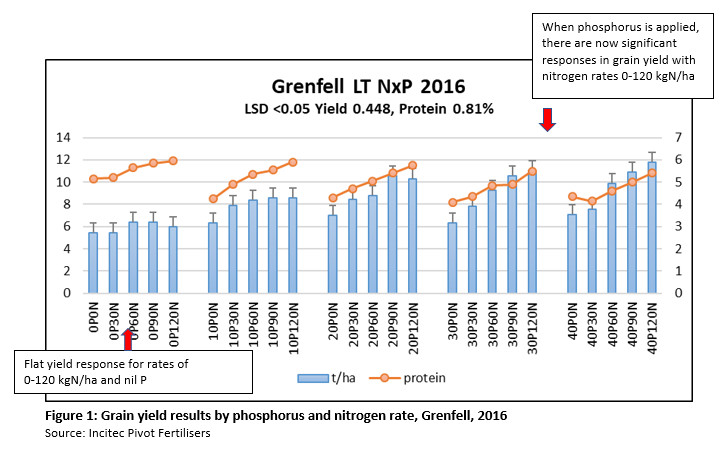

There is a large bank of evidence from long-term trial sites, including Dahlen in Victoria and Grenfell in New South Wales, to show that applying phosphorus may optimise yields, when used in balance with other nutrients. At the Incitec Pivot Fertilisers long-term trial site in Grenfell in 2016, grain yield responses to nitrogen were only achieved where phosphorus was in adequate supply. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Grain yield results by phosphorus and nitrogen rate, Grenfell, 2016

Phosphorus requirements for 2019

So, to the key questions for 2019:

- Can we modify phosphorus rates after a drought year and rely on previous fertiliser applications?

- Will reduced rates effectively provide adequate readily available phosphorus to emerging crops?

Yes, it may be possible to reduce rates. Residual phosphorus from drought years has in the past contributed to the success of the following year’s crop. But there are a few ‘ifs and buts’.

The decision making process starts with knowing the phosphorus status of the surface soil (0-10 cm depth). The test should be a locally calibrated soil P test (extractable soil P) and include the phosphorus buffering index (PBI).3

Consider the fertiliser rate used in 2018. Was it high or low? If it was already low, there might not be adequate carry over for the 2019 cropping program.

It will also depend on the amount of fertiliser used and removed by the 2018 drought affected crop, which will vary. Where crops were cut for hay, removal rates may be higher than those harvested for grain. See Tables 1 and 2. A failed crop which yielded less than 0.5 t/ha and was harvested for grain with stubble left standing is likely to have left more residual phosphorus in the soil than a crop which yielded more than 0.5 t/ha.

|

|

N kg/t |

P kg/t |

K kg/t |

S kg/t |

|

Frosted wheaten hay (15% moisture) cut at milky dough stage |

17 |

2.3 |

28 |

1.9 |

|

Green manured canola (50% moisture) cut 7 days before planned windrowing |

17 |

2.4 |

24 |

4.6 |

|

Harvested wheat – not frost affected |

2 |

0.3 |

12 |

0.4 |

|

Harvested wheat – frost affected |

7.5 |

0.5 |

21 |

1.9 |

Table 2: Examples of wheat grain nutrient removal in dry weight, Grenfell long term trial, 2018

|

Trial treatment |

N kg/t |

P kg/t |

K kg/t |

S kg/t |

Ca kg/t |

Mg kg/t |

Cu g/t |

Zn g/t |

|

20P/60N |

26 |

2.3 |

3.5 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

3.6 |

26 |

|

40P/120N |

27 |

3.0 |

3.9 |

2.1 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

4.4 |

28 |

Assuming there is some residual plant available fertiliser phosphorus left in the sowing band, it may be possible to halve starter fertiliser rates, but only if you can effectively target last year’s fertiliser band without it being thrown into the inter-row by the planting tynes. Disc seeding systems with minimal soil throw may be more effective accessing residual banded phosphorus from the 2018 application. Also, if planting wheat on wheat, consider the potential for high levels of crown rot carry over in last year’s plant line.

At rates lower than 5 kg/ha of P (23 kg/ha MAP at 40 granules per gram) on 25 cm row spacings, there will be less than 23 granules of fertiliser per linear metre. That’s one fertiliser granule approximately every 4 cm.

Remember that some of the applied phosphorus will also have moved into the soil phosphorus pool and become unavailable. This is more likely in calcareous soils and where soil PBI levels are greater than 140. Wind erosion and dust storms from this summer are another potential phosphorus loss pathway to consider.

Also think twice about cutting rates if sowing late into cold soils. This is one situation where water soluble phosphorus is needed to assist with strong crop establishment.

In summary:

- Phosphorus rates may be reduced to a maximum of 50% where crops have failed (<0.5 t/ha) in the previous year, provided yield potential is low for 2019 due to low nitrogen status or high disease risk.

- Phosphorus rates may be reduced by up to a third when the drought affected crop yielded more than 0.5 t/ha, unless soil phosphorus levels are very low.

- Phosphorus rates may be reduced where the paddock has had a good phosphorus history over time. There will be less response to fertiliser phosphorus where soil phosphorus levels are above recognised district critical levels.

What about from a soil fertility perspective?

If paddocks don’t have any recent soil test results, the Nutrient Advantage® laboratory has a wide range of soil test programs to suit all situations and budgets. A comprehensive soil testing program segmented to depth can also assist in identifying any sub-soil constraints that may limit production potential.

When reviewing the soil test data consider:

- What is the regional calibration data for crop type, soil type and yield potential?

- What is the relationship between soil test and quantity of fertiliser needed?

- What is the likely economic benefit of the fertiliser or soil ameliorant application?

It is essential to know your soil’s phosphorus status before considering a rate cut this season. Soil test (0-10 cm) to see whether soil fertility is adequate for your targeted yields. Until there is evidence to support alternative sampling strategies, the recommendation is to take 20-30 soil cores across a defined area in a random pattern at 0-10 cm depth.

If soil testing from this autumn shows phosphorus levels are above recognised district critical levels, this will give you some breathing space to potentially modify starter fertiliser rates. There may be a greater response to starter fertiliser where soil phosphorus levels are less than the recognised district critical levels.

Phosphorus is the foundation of any successful winter crop. Growers who know their soil phosphorus levels and supply adequate phosphorus at sowing are giving themselves every opportunity to maximise returns at the end of the season. In contrast, applying too little phosphorus, on paddocks with low levels of phosphorus fertility, will limit crop potential.

Where there are budget considerations, my best advice is to be prepared to take a paddock by paddock approach when planning starter fertiliser rates, rather than using a flat rate across the whole farm. Don’t skimp on the best paddocks – that first crop out of fallow or pasture, or the paddocks known to have good soil nitrogen levels and no weed or disease problems, no soil physical or chemical limitations. These paddocks will potentially offer the highest yields and best returns on the investment in phosphorus.

Keep in mind the potential income from yields that may be lost if rates are reduced too much. Calculate the cost savings. Then calculate the potential lost returns from the reduced yield.

For more information and advice, see your local fertiliser adviser to discuss and arrange soil testing, or feel free to contact me on 0427 006 047 or jim.laycock@incitecpivot.com.au.

References:

1 Australian soil fertility manual, J.S. Glendinning, CSIRO Publishing, 1999

2 Bolland MDA (1999) Decreases in Colwell bicarbonate soil test P in the years after addition of superphosphate, and the residual value of superphosphate measured using plant yield and soil test P. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 54: 157 - 173

3 Reuter McLaughlin Armstrong Fertiliser P management after the 2006 drought